原创: Joshua Freedman

How to Understand People: Ask, Listen, and Get Real

如何理解他人:提问、倾听和真诚

Do you want to know how to understand people better? Then you need to get better at understanding emotions. A starting point is to examine a wide-spread lie we tell others — and ourselves.

你想知道如何可以更好地理解他人吗?那你需要首先学会更好地理解情绪。先从审视我们经常告诉他人和自己的一个谎言开始。

A misleading exchange takes place a billion times a day: “Hey, how’s it going?” “Great, thanks. You?” “I’m fine!” Has communication occurred, or been blocked?

一段具有误导性的对话每天都要在世界各地上演数十亿遍:“嗨,你好吗?”“很好,谢谢。你呢?”“我也很好!”这样的对话到底是产生了交流,还是阻碍了交流?

In this barrage of “checking in,” there’s no real exchange of information, but there is a mutual deception. In asking the question, we pretend that we’ve actually seen and heard the other. In answering, we’ve followed convention but hidden our experience. Why? Safety. It’s “normal,” which means it’s comfortable. Speed. It’s fast, which means we don’t need to get caught up. Script. We all know we’re “supposed to” stay on the surface, so we do.

在这种“寒暄”的情境下,双方并没有真正的信息交流,而是在相互欺骗。提问的人假装自己真的看到和听到了对方的答案。回答的人也只是在遵循惯例,而隐藏了自己的真实感受。为什么呢?因为安全。因为这样才“正常”,才会让人觉得舒服。因为速度。这样可以很快地结束对话,我们就不必被困住。因为客套。我们都知道我们“理应”表面客套一下就好,于是我们就这么做了。

No Blood, No Foul?

无害不罚?

So what? We’re following a social convention — and isn’t it better than simply ignoring the other person? The risk of this surface non-communication is the illusion of inquiry. If we walk out from this “discussion” pretending we’ve actually understood, we block the real data that’s available. I suspect that as this surface transaction has become the cultural norm, simultaneously we’ve found it increasingly difficult to have more substantive dialogue. “Norms,” by definition, are what’s comfortable. What’s proper. What’s prudent. So we’ve become used to a shallow exchange, and this leads us to miss invaluable data. It’s no wonder so many of us struggle with how to understand people. As George Bernard Shaw famously said,

那又怎么样呢?我们是在遵循一种社会惯例——而且这难道不是比直接忽视对方更好吗?这种表面客套的风险是让人产生询问的错觉。假如我们结束这段“讨论”,假装自己已经懂了,那我们就屏蔽了可用的真实信息。我怀疑,因为这种表层交流已经变成了文化习俗,导致我们越来越难以进行更加实质性的对话。“习俗”的定义就是让人感到舒适、得体、谨慎的行为。所以我们已经习惯了浅层的交流,这导致我们会错失一些宝贵的数据。这也就难怪我们很多人都觉得难以理解他人了。正如乔治·萧伯纳所言:

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

“沟通的一个最大问题就是让人以为它已经发生了的错觉。”

Don’t fall in that trap. Remember this secret: There is always more to the story. And if you really want to know how to understand people better, you have to dig deeper. You have to really ask how they are feeling, and invest in understanding emotions.

不要陷入这个陷阱。记住这个秘密:事实远不止此。如果你真的想要知道如何才能更好地理解他人,你就必须更加深入地去寻找答案。你必须真诚地询问对方的感受,并用心地去理解情绪。

The first step to understanding others is to open yourself up to really finding out。

理解他人的第一步是打开自己去真诚地寻找答案。

How To Ask About Feelings

如何询问他人的感受

Nearly 20 years ago, I was teaching about the Vietnam war, and talked to one of the veterans who counseled other vets. I explained that my dad was a veteran, but he’d never told me about his experience in the war. The counselor asked, “When are you asking him? On the way to the airport? In a busy restaurant? You just can’t give a real answer to that question unless you’re sitting by a lake with a case of beer and a whole weekend ahead of you.” The more complex and challenging a topic, the more time and space will be needed for a real answer. If I’m going to be vulnerable enough to reveal something ugly, scary, painful, serious — or even just complicated — I’m not going to do it in a casual, hurried, public setting. I’m not going to talk if I can tell you don’t have time. And, if you want me to be honest about my experience, let’s go real. It’s back to those 3 Ss:

大约20年前,我正在教授有关越南战争的课程,所以去与一名为其他退伍军人提供心理咨询的老兵谈了谈。我解释说,我父亲也是一名退伍军人,但他从未向我讲过他在战争中的经历。那名咨询师问我:“你是什么时候问他的?在去机场的路上?还是在喧闹的餐厅里?除非你们是坐在湖边,旁边备着一箱啤酒,并且空出了整个周末的时间,否则他根本没法真正地回答这个问题。”越是复杂和具有挑战性的话题,越是需要更多的时间和空间来认真地回答。如果我要脆弱到足以去讲述丑陋、可怕、痛苦、严重、甚至只是复杂的事情,那我不会在随意、仓促的公共环境中去做这件事。如果我能看出来你没有时间,那我就不会打开心扉。而且,如果你希望我对自己的经历和盘托出,那我们就要坦诚相待。这就回到了那三个S:

Safety: Start by building a trusting relationship; ask questions that are appropriate to the level of trust… or trust plus one, by which I mean pushing the boundary and asking a slightly more serious question than yesterday’s question. Also, make sure there’s sufficient privacy and time for the seriousness of the question. Pull someone aside, go for a walk, sit side-by-side, make a space.

安全:从建立信任关系开始;提问的问题要符合你们之间的信任水平……或者信任水平+1,即突破边界、提问一个比昨天的问题稍微严肃一些的问题。此外,要确保给对方留出足够的隐私和时间来应对问题的严肃性。把他拉到一边,一起走一走,并排坐下,或者创造一个空间。

Speed: More serious conversations take longer. Find five minutes for a five-minute-level check-in. Make an hour for a much more serious one. If you’re in a rush, people feel that, and they’ll conform to the “I’m in a rush” signal you’re sending (or, if they don’t they might need to learn that norm…)

速度:越是严肃的谈话需要的时间就越久。如果是五分钟水平的寒暄,那空出五分钟的时间就好。而如果是更为严肃的交流,请留出一个小时的时间。如果你很匆忙的话,对方会感觉到,然后他们就会配合你发送出来的“我赶时间”的信号(如果他们不这么做的话,也许他们该学学这种社交礼仪了……)

Script: While “surface” is the starting norm, the way you respond tells the other person what to expect next. If they perceive that you’re following a script, you send a message that this isn’t real. If you invalidate their ideas and feelings at the outset, they “know” not to be honest. If you push or pull, they “know” this isn’t a real dialogue. On the other hand, if you take turns, sharing, asking, listening, recognizing, reflecting… as the dialogue flows back and forth, it also flows beyond the surface.

客套:虽然流于“表面”是开始对话的常规方式,但你的回应方式却会告诉对方接下来该怎么做。如果他们认为你只是在说客套话,那你就向他们发送了一条消息,告诉他们这并不是真正的交流。如果你从一开始就否定他们的想法和感受,他们就会“明白”不必坦诚相待。如果你东拉西扯,他们就会“明白”这不是真正的对话。而如果你们能够轮流分享、提问、倾听、认同、反思……对话内容有来有往,那这就是超越表面的交流。

Communication Exercise

交流练习

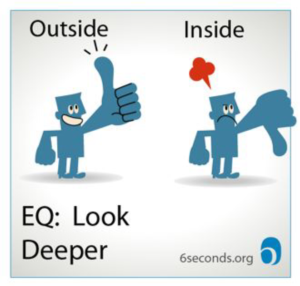

In any moment, consider there’s the “outside story,” or what we’re comfortable sharing… and the “inside story,” what we’re really thinking and feeling. Here is one of Six Seconds’ training exercises that you can use to explore this for yourself — with a partner — or even in a group. All you need is a paper and something to write with, but it’s more fun with colored pencils or pens:

任何时候都要记住,除了“外在故事”(即我们乐于分享的内容)之外,还会有一个“内在故事”(我们的真实想法和感受)。以下是六秒钟的一个培训练习,你可以利用这个练习与一名搭档甚至组成一个小组来一起探讨这个问题。你只需要一张纸和任何可以写字的工具即可,不过用彩色的铅笔或钢笔会更有趣:

Step #1

第1步

Think of a situation, perhaps a recent conversation that was somewhat complex. Or maybe a party you attended, or a meeting, or even just walking into school or the office.

回想一个情境,比如最近发生的一段有些复杂的对话,或者你参加过的一个派对或会议,甚至是去上学或上班路上的时刻。

Step #2

第2步

On one half of your paper, make a sketch or symbol of what you were showing on the outside. On the other half, represent what you were feeling on the inside.

在纸上一半的地方,画出一幅草图或者一个符号,代表你对外呈现的样子。在另一半纸上,画出你内心的真实感受。

Step #3

第3步

Discuss – and this is “where the magic happens.” Of course, the skill of your facilitator or partner is what makes this either interesting or amazing. Depending on the situation, questions could include:

讨论——这也是“见证奇迹的时刻”。当然,讨论的有趣程度取决于你的讲师或者搭档的能力。根据情境的不同,讨论的问题可以包括:

- Are the two sides different?

- 这两面有所不同吗?

- What are some differences?

- 具体有什么区别?

- Why do you suppose that is?

- 你认为这样的原因是什么?

- What would happen if you were to show more of the inside (if you didn’t)? What are the costs and benefits of doing that?

- 如果你更多地表达自己内心的真实感受(如果你还没有这样做的话),会发生什么情况?这样做会有什么代价和收益?

- How would it affect you — and others — and your relationships?

- 这会对你和他人以及你们之间的关系有何影响?

This can go quite a bit further — about self-awareness, about patterns, about choices and consequences, and even about purpose. What kind of relationships do you want to build? Why does that matter? What choices will you need to make for that to happen?

我们还可以更进一步——去探索自我意识、情绪模式、选择与后果、甚至目的和意义等。你希望建立什么样的人际关系?为什么那很重要?你需要做出怎样的选择才能实现这一目标?

The Point: Look Deeper

结论:深入了解

If you want to understand others, you need to get beneath the surface and start understanding emotions. If you fool yourself into believing the surface story, you’re missing invaluable data.

如果你想理解他人,那么你需要深入表层以下,试着理解对方的情绪。如果你自欺欺人,选择去相信表面的故事,那你就会错失许多宝贵的信息。